India’s rural heartland is quietly transforming into a powerful economic engine. What was once viewed as purely agrarian territory is fast becoming the stage for one of the country’s most promising growth stories — rural tourism. With travelers seeking authenticity, policymakers promoting inclusive growth, and investors eyeing untapped opportunities, this is a sector on the cusp of acceleration.

The Shift: From City Escapes to Village Experiences

The modern Indian traveler has changed. Post-pandemic, there’s a clear preference for slower, more meaningful experiences — homestays, village walks, crafts, and farm life — instead of conventional city hotels. This shift has economic depth. According to Future Market Insights, India’s sustainable tourism market, which includes rural travel, is projected to expand from USD 37.1 million in 2024 to USD 216.7 million by 2034, growing at a rapid 19 percent CAGR.

The government has taken notice. Initiatives such as the National Strategy for Rural Tourism and Swadesh Darshan 2.0 are being expanded to support “tourism circuits” connecting India’s villages. These programs are not just about travel; they are about creating micro-economies that generate jobs, boost rural income, and reduce migration to cities.

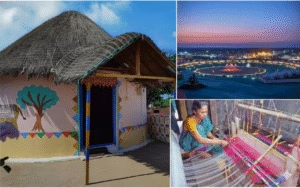

Dhordo, Gujarat: From Desert Silence to ₹468 Crore in Revenue

Few examples illustrate this shift better than Dhordo, a once-isolated desert hamlet in Gujarat’s Kutch district. Recognized by the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) in 2023 as one of the world’s Best Tourism Villages, Dhordo now attracts more than half a million tourists every year — a stunning leap from fewer than 7,000 just a few years ago.

Its transformation is anchored around the Rann Utsav, a festival of desert culture that has become a global attraction. The Gujarat government reported that this single event generated ₹468 crore in GST revenue in FY 2022–23. For investors and entrepreneurs, Dhordo shows how branding, infrastructure, and community participation can turn a barren land into a high-yield seasonal economy.

The lesson is clear: when culture is marketed as an asset, even remote areas can become revenue-generating ecosystems.

Kiriteswari, West Bengal: Spiritual Heritage as Economic Catalyst

Across the country, Kiriteswari village in West Bengal’s Murshidabad district is another remarkable success. Chosen as India’s Best Tourism Village for 2023 by the Ministry of Tourism — from among 795 national entries — it’s a living example of heritage tourism driving rural income.

Home to nearly 25,000 residents, Kiriteswari blends religious diversity, local craft, and deep cultural heritage around its historic Shakti Peetha temple. Tourists arrive for spirituality, but stay for the experience — witnessing traditional weaving and local cuisine.

For small entrepreneurs, the model here is a mix of heritage-based homestays and craft-linked tourism. Financially, it offers two revenue channels: accommodation and local product sales. What Kiriteswari proves is that small-scale cultural tourism, when packaged well, can become a steady livelihood source.

Maniabandha, Odisha: The Loom That Weaves Growth

In Odisha’s Cuttack district, the Maniabandha village has turned centuries-old craftsmanship into a contemporary tourism success story. In 2024, it was awarded India’s “Best Tourism Village” in the Crafts Category.

Here, more than 520 Buddhist families are engaged in traditional Ikat handloom weaving. Tourists can observe artisans at work, learn about eco-friendly silk processes, and buy directly from the weavers. This “craft plus stay” model minimizes operational costs and maximizes community benefit — a textbook case of inclusive entrepreneurship.

From a financial lens, the opportunity lies in value stacking: pairing accommodation income with direct craft sales, workshops, and online exports. For investors or creators looking for social impact and return, Maniabandha offers both.

Hodka, Gujarat: The Community-Owned Business Model

A few hundred kilometers from Dhordo lies Hodka, another rural village in Kutch that’s now studied in tourism-management courses for its innovation. Supported by the UNDP and India’s Ministry of Tourism, it pioneered community-owned hospitality under the “Endogenous Tourism Project.”

The results were striking. As early as 2013, one small resort in Hodka — run by local families — reported annual revenue of about ₹45 lakh. Today, Hodka’s eco-resorts and mud-hut homestays continue to attract cultural tourists and photographers seeking authentic desert life.

The financial takeaway here is scale with sustainability. Instead of corporate hotels, Hodka thrives on local ownership, meaning profits circulate within the community — an appealing model for CSR, impact investors, and social entrepreneurs.

Malarikkal, Kerala: Where Water Lilies Bloom Into Business

In the southern state of Kerala, Malarikkal village near Kottayam is redefining what rural tourism can look like. Known for its vast 2,700 acres of water-lily-covered paddy fields, this once-quiet farming area now draws visitors for its photogenic landscapes and tranquil boat rides.

According to The Times of India, boat operators here earn between ₹4,000 and ₹5,000 per day during the bloom season. The Kerala Tourism Department has since identified Malarikkal as a model “village tourism” destination — combining agriculture, ecology, and aesthetics.

For small investors, the area offers possibilities in eco-retreats, guided photography experiences, and agri-tourism packages. Its success underlines a key point: nature-based tourism can complement farming income, turning environmental stewardship into enterprise.

The Business of Belonging: Why It Matters

These stories, spread across India’s diverse geography, reveal a clear pattern — rural tourism is moving from experiment to enterprise. It is building real revenue streams, attracting government incentives, and inspiring a new kind of entrepreneurship rooted in sustainability and culture.

India has more than 7 million villages, with over 70 percent of its population still living in rural areas. If even a small fraction — say, half a percent — becomes tourism-ready, that translates to thousands of micro-businesses across crafts, homestays, and local experiences. Analysts predict that rural tourism could soon contribute up to 3–4 percent of India’s total tourism GDP, with direct benefits flowing to village households.

Challenges and the Road Ahead

Despite the promise, challenges remain. Many villages still face infrastructure gaps — from poor road access to limited sanitation and patchy internet. Seasonality is another concern; while some destinations flourish in winter or bloom seasons, they experience off-peak slowdowns.

There’s also the risk of over-commercialization. When tourism grows too fast, it can erode the authenticity that draws visitors in the first place. To prevent this, policymakers and entrepreneurs must balance growth with conservation — ensuring that villagers remain stakeholders, not bystanders, in their own success.

The Financial Future of Rural India

Rural tourism aligns with India’s long-term financial and social goals — job creation, rural income diversification, and sustainable growth. It’s also low-barrier: one homestay, one craft collective, or one cultural circuit can start small and scale over time.

As the government expands rural connectivity and travel infrastructure, this sector offers a rare intersection of profit and purpose — appealing to investors, creators, and communities alike. From the salt flats of Dhordo to the pink wetlands of Malarikkal, India’s villages are writing the next chapter of economic inclusion.